Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the second installment.

Last time I pointed out the brilliance of the first few issues of Miracleman, even with all that gaudy color slapped on top of Garry Leach and Alan Davis’s awfully nice black-and-white artwork. Also, I’m going to continue to refer to Miracleman as “Marvelman” as I discuss the final few chapters of the Warrior-era reprints and we transition into the original material published by Eclipse.

Seriously, he’s Marvelman, contrary to what it says on the cover. Curl up in a fetal position inside your sensory deprivation tank. Everything will be all right.

Miracleman #4 (Eclipse Comics, 1985)

I neglected to mention an important plot point when I was discussing the first three issues of this series. Liz Moran, wife of Mike Moran (aka Marvelman), is now quite pregnant. Not by her husband, but by her husband’s superhuman counterpart. And since the series establishes that, while in Marvelman form, Moran’s consciousness is actually piloting an alien, god-like superbeing, that means that Liz has been impregnated with some seriously powerful extraterrestrial DNA. Her pregnancy looms over everything that happens in this issue, and the ones that follow.

The first story in this issue, “Catgames,” is a bit clumsier than Moore and Davis’s previous efforts. The art is a bit stiff, and it sets up a cliché-ridden parallel between Marvelman and a jaguar. The hero is the “big game” for Emil Gargunza, get it? Yeah, it’s heavy-handed in a way that Moore had avoided in the previous installments, most of which were non-stop surprises and narrative high-wire acts.

This one does have a little bit of terror inside Johnny Bates’s mindscape, but that doesn’t redeem the flatness of the rest of this opening chapter. It’s a perfunctory installment, setting up the Marvelman/Gargunza confrontation.

The following chapter is even worse, with a plot contrivance Marvelman takes some time to talk to a kid in the woods, and show off his powers just convenient enough to get the hero out of the way so his wife can be kidnapped. A more generous reader might reflect on this sequence and see Moore’s commenting on the traditional role of the female love interest as eternal victim. But after the impressive feats of the first three issues, this fourth issue of the reprint series is just one misfire after another. I’m always loathe to concern myself with biographical details when I’m reading or rereading a text, but I can’t help but think that these Marvelman installments were produced by an Alan Moore who had quickly overextended himself by working on four simultaneous serials (Marvelman, V for Vendetta, Captain Britain, and Skizz) and a bunch of short stories only a few months after kicking off this phase of his career.

This isn’t his best Marvelman stuff, though the issue does end with two high points. The first one is the final scene between Gargunza and Liz Moran, in which we see his truly sinister intentions: using the “Marvelbaby” as the vehicle for his own consciousness. Unsettling, indeed. And the second high point is the inclusion of a Marvelman Family interlude, drawn by John Ridgway, where we flash back to the time when Marvelman, Young Marvelman, and Kid Marvelman were still hooked up to machines in Gargunza’s bunker, dreaming of themselves as superheroes. Their dreamworld manifestations of their physical imprisonment and victimization leads to some haunting moments.

Moore redeems the issue in the end. Which is good, because when readers go through the trouble of tracking down these long out-of-print issues, they don’t want Moore at his worst. They don’t want to see that until the mid-1990s at least.

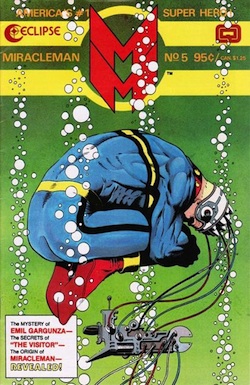

Miracleman #5 (Eclipse Comics, 1986)

By issue #5 Moore has slipped off the comfortable blanket of superhero narrative, and the true nature of the Marvelman horror story begins to come into focus. And it is a horror story, with its mounting tension, it’s inevitable but delayed violence, and with a fetus looking up at us through the pages of the comic book.

That’s an image you’ll not soon forget, and Moore and Davis pace that scene perfectly to conclude the first chapter of this issue.

Throughout issue #5, we basically get the Emil Gargunza story, and while he’s no sympathetic character, Moore does humanize his villain by showing what led him to his scientific pursuits, and what made him become the man who could torture a bunch of young men and boys and play around with alien technology for the sake of his own curiosity.

A lot of the particular plot details rehash some of the things we’ve learned in abbreviated form in previous chapters, but we get a new perspective on it here and it helps to crystallize the narrative and make it more satisfyingly comprehensible. Marvelman, at least for the first handful of Eclipse reprint issues, is a dense story, made more visually packed because the magazine-size artwork is rescaled to fit the smaller comic book page. So when information in the series becomes a bit recursive, that’s not a problem at all. It helps to keep the reader on track. And it works.

This issue concludes with a follow-up to the previous issue’s “Marvelman Family” flashback, again drawn by John Ridgway, whose delicate crosshatching adds a ragged but airy quality to the tale. Thematically, it provides a doubling-down on the Gargunza-as-puppet-master scheme, and we see the subconsciousness of the “dreaming” Marvelman adapt to his real-life situation by folding the scientist Gargunza into his superhero world as his arch-villain. Gargunza, in the bunker with the slumbering superhumans, closes out the issue with a look for panic on his face. He has now become part of the fictional story he has implanted on his human lab rats. And that’s a dangerous place to be.

It’s a horror story, remember?

Miracleman #6 (Eclipse Comics, 1986)

When Alan Moore and Alan Davis walked away from Warrior with issue #21, a few months before the magazine folded, they not only left the readers with a cliffhanger, they left the readers with a cliffhanger that was also the climax of the Marvelman/Gargunza confrontation.

Luckily, Moore was able to continue the story in America, at Eclipse Comics, so readers only had to wait a year or so to see its resolution.

The downside is that Alan Davis didn’t join him for the concluding chapters, but I’ll get to that in a minute.

First: Miracledog!

The final Warrior chapter begins this issue, and Moore doesn’t give us a Marvelman vs. Gargunza slugfest. This isn’t Superman vs. Luthor or Captain Marvel vs. Sivana, which, in either case, would have led to punches thrown and laser robots and something hovering and probably big machines and science. Instead, in this superhero-comic-that’s-really-a-horror-comic, we get a verbal killswitch and a transformation. “Kimota!” was no magic word, just a triggering mechanism for the consciousness shift. Gargunza has his own trigger to undo the transformation. To turn Marvelman into a wrinkled, tank-top-sporting, paunchy Mike Moran.

“Abraxas,” he says. And that’s the end of Marvelman.

“Steppenwolf,” he says. And that’s where Gargunza’s puppy turns into a gigantic green quadruped.

A quick aside for fans of annotation: the word “Abraxas” alludes to a Gnostic concept of a higher god. “Steppenwolf” is likely a reference to Herman Hesse’s novel about identify, metaphysics, and magic, or maybe it’s just a shout-out to the “Born to be Wild” guys. That Gargunza would step outside the God/Devil duality (or the superhero/supervillain duality) and provide an anticlimax to the confrontation by summoning Abraxas, even symbolically, is fitting, and shows a playful Moore having some fun with superhero comic book conventions. The Hesse thing is likely just a joke. Though a magic carpet ride is not out of the question.

And that’s where the original Marvelman serial leaves us, but within this very issue, the story continues, with new art, new comic-book-sized layouts, and new bubbly word balloons that can’t help but make the Eclipse material look more like a parody of Marvelman than an actual Marvelman story.

It doesn’t help that Moore’s artist for the new material is one Mr. Chuck Beckum, a young artist who lacked the capacity to live up to any subtlety necessary for Moore’s script and lacked the drawing chops to compete with the Garry Leaches and the Alan Davises who preceded him. Beckum, later in life, became known as Chuck Asten, and carved himself a brief but memorable career as a comic book writer, on titles like Uncanny X-Men and Action Comics, before being driven out of comics by angry message board fans.

That last sentence might be a bit of an exaggeration, but it’s not too far off from the accepted story of his departure from comics. I don’t know what really happened, or what caused him to walk away from the industry later in life, but I do know that as a Marvelman artist and I suppose I really should call the character Miracleman for this new stuff, but I refuse Chuck Beckum is pretty terrible.

His sins, on the page, enumerated: (1) his characters have dead eyes, a real weakness in a story that’s an attempt to add human dimensions to a horrific superhero story; (2) his “Miracledog” is less an imposing alien monstrosity and more a lumpy-carapaced giant grasshopper. It does some bad stuff later in the story, but it looks mostly goofy throughout; (3) Evelyn Cream, as drawn by Alan Davis, had personality and a flabby, fleshy substance to contrast with his indimidating confidence. Beckum draws him with jagged abs and a square jaw, as if he’s never even seen Davis’s version or is incapable of drawing anyone who isn’t a weird, musclebound action figure. Gah, it’s atrocious; (4) the tragic death of Cream, who has developed into quite a sympathetic character by this point, is structured by Moore in a too-clever-by-half kind of way involving a close-up fake-out, but Beckum totally botches it anyway, making the decapitated character look even more ridiculous than he should.

John Ridgway draws a nice silent Young Miracleman story as a back-up feature in this issue, but, then, what’s this? A pin-up by Chuck Beckum. Well, that doesn’t look half bad. I wonder if that’s the kind of thing that landed him the job. Maybe his work isn’t so abominable after all. Let me flip back a few pages and

Oh, it’s really bad.

So much for this Alan Moore masterpiece. So much for the fans who read Warrior through issue #21, found an unfinished story, and then waited in eager anticipation for this.

The lens of history tells us that Beckum didn’t last long on the Miracleman series. Soon we’ll get proper artists Rick Veitch and John Totleben and Alan Moore’s first major comics work will get a decent ending. We know this to be true.

But issue #6, and Chuck Beckum, they must stand as one of the most crushing disappointments in the history of the universe. Is that too strong? It is Alan Moore. It is Marvelman. They demand hyperbole.

NEXT TIME: Marvelman/Miracleman Part 3 Veitch, Totleben, and More Moore

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.

Honestly, I always liked the kid-in-the-woods scene. The “are you a pouf, or are you a nero?” line was the point of it, to me, and I think it’s an excellent question in its several entendres, and one that embeds a considerable amount of social commentary.

Incidentally, you’re always loath to concern yourself with biographical details, not loathe. Loath is an adjective, loathe is a verb. Sorry to be That Guy, but this error is getting endemic.

I don’t have access to these comics at the moment, and am trying to follow your re-read but was left ultimately confused by your description of issue five. Having not read it myself I expected some sort of short recap about what happened, but all I’m seeing is a confusing statement about a fetus. What happened to the baby? What happened to his wife, for that matter, if there’s a fetus on the loose? Did Gargunza succeed in using the Marvelbaby as a conduit of his consciousness, as you mentioned? I just kind of feel confused about what happened in this batch of issues from your descriptions, where I felt it was made very clear in your inaugural post.

Love your re-read. Miracleman has alwas been one of my favorite comics… I found Eclipse’s issue #2 in a dusty bin in some obscure comic shop here in Mexico in the ’90s, read it and quickly became obsessed about this strange little tale that subverted almost everything about traditional superhero storytelling…

I managed to find almost every Eclipse issue (except for 11 and 12) and was properly awed by the scope of the whole thing. I cannot wait for the review of the infamous issue #15… ;)

There’s a also a little backup story (in LaserEraser #2, I think) by Moore and Leach called “Cold War, cold warrior” featuring the warpsmiths, which will later figure so importantly in Miracleman’s tale… Will you include it in your reviews? I think it provides some nice context about the nature of the… interactions between the Qys and the warpsmiths… Plus, it’s damn good and the art is spectacular…

Gah. I’m loving this re-read, and hating the fact that these issues aren’t in print anymore (as far as I know) and that I can’t read them for myself. It’s probably the only major Moore comic that I dont’ have a copy of, becuase you can’t buy a copy of it anymore.

I really really really hope Marvel manages to get its act together and re-print these. I will buy them immediately.

“Cold War, Cold Warrior” was originally in Warrior. There’s a third Warpsmith story, “Ghostdance”, that was in the anthology A-1. There’s also a missing chapter in the first book, “The Yesterday Gambit”, that never has been reprinted in the US…

(But this is probably not going to be a truly complete re-read. I certainly hope not to see a week’s post wasted on “Maxwell, the Magic Cat” or “The Bowing Machine”. Although I wouldn’t mind one on his American Flagg story when we get to that time-perioud…)

Yeah, it’s not a complete reread, but I am going to cover all the big stuff and some of the ancillary work (like his Star Wars shorts, and some of the lesser DC bits).

Zeta — I’m not going to summarize everything, but I will do my best to make sure that you get the important info. And the stuff about the baby will be addressed later, so you’ll get caught up. I’d rather prioritizer my reaction/analysis/evaluation in these posts than simply retelling plot points.

And once I get to V for Vendetta, I hope everyone can start reading along, since there will be a nice stretch of stuff that’s easily available (V and the Captain Britain stories, for example).

Thanks everyone!

ZetaStriker: It’s still an unborn fetus at this point in the story, and Gargunza is monitoring it. But he finds that it also seems to be aware of him, which is, as Tim says, a rather creepy moment.

Tim: “Abraxas” is also a Hesse reference; see Demian. It’s pretty funny for Gargunza, who hates mysticism and wants to live forever, to be a fan of Hesse– a Romantic mystic for whom accepting death was a form of transcendence. Presumably he read those books the same way I did as a teenager, i.e. just getting off on the general “you are a special person with secret knowledge” part.

Also, a post-Moore footnote: the “kid in the woods” scene in #4 does sort of read as an arbitrary digression the first time around, but Neil Gaiman’s Miracleman: The Golden Age has a nice callback to it that (as with many of Gaiman’s Moore-scrap-repurposings) makes it seem in retrospect like it had a purpose all along. IMO.

Tim: Also, not that you have to mention everything, but there’s another nice bit in issue 5 that’s relevant to your point about this being a horror story: Cream blackmails his former boss Archer by saying that MM will personally destroy London. For me, this was where the horror aspect really kicked in, because although we’d already seen Bates being a monster, all of the violence in that chapter was one-on-one; here Moore is reminding us that someone with Superman-ish powers would be able to kill millions of people in a short time with his bare hands. (Up till then, the movie Superman II was the closest thing to a depiction of somewhat dangerous-looking superhero combat in a big city, but still almost no one got hurt in that.) MM is just as dangerous as Bates, except that he’s the good guy– but Archer clearly doesn’t think that’s a sure thing, since his reaction is not “Marvelman would never do that!” but more like “OMG PLEASE NO.”

Nice point Eli! I didn’t even catch the significance of that moment, but you’re absolutely correct.

Re the name “Miracleman”– I was surprised to discover that name (well, “Miracle Man”) was actually originated by Marvelman’s creator Mick Anglo, who apparently was into recycling before it was cool. Anglo sold redrawn Marvelman strips (with a different costume) in Spanish-language markets (as “Super Hombre”– no idea if that led to a recapitulation of the Fawcett/DC dispute in those countries).

Then– waste not, want not!– relettered the redrawn strips in English and sold them as Miracle Man (aka Johnny Chapman, who changed to his heroic identity with the word “Sundisc”).

Then in the 60s he went to the well again with “Captain Miracle”, aka Johnny Dee, who changed to his heroic identity with the “magic eastern formula” “El Karim” (which, like “Kimota”, suggests Anglo liked writing words sdrawkcab :-) ). Evidently, Moore was following his source material in subbing Miracles for Marvels.

(All info from internationalhero.co.uk– I’d link directly, but I’m not sure if that would trip a spam filter.)

Warrior #21, with the last installment of Marvelman, was published around August 1984. Miracleman #6, with the next installment, was published around February 1986. That seemed like a crushingly long wait at the time, but we hadn’t seen what was yet to come on that score.

As to “One of Those Quiet Moments”, it was just what it set out to be: a look at what superheroes are like in quiet moments. At the time, it seemed–not exactly “revolutionary”, but still a significant change in perspective.

By the time of Watchman, Moore was noted for giving his artists exceedingly detailed accounts of what they should draw, frame by frame. Was he doing so already during Miracleman? Or is it a trait that came latter, possibly as a product of dealing with such different artists on one project?

Not so incidentally, I though at first revisiting (or visiting for the first time) a batch of comics was a silly idea, even if they were Alan Moore’s comics. I’ve changed my mind. I’m liking this a lot and the credit’s entirely due to you. Thanks for doing this.

Moore was writing very detailed descriptions as early as Swamp Thing–I’ve seen the scripts to a couple of issues of that and while they’re not quite as epic as either Watchmen or From Hell, they’re very detailed.

I suspect he started with the long scripts no later than V for Vendetta–look at the backgrounds of the first installment of that and notice how much information is jammed into the movie posters in V’s dressing room.

Some really good comments on a post by The Beat with regards to the decision to bring Chuck Beckum in as penciller. None other than Dez Skinner and Dean Mullaney themselves note that it was Alan Moore who brought in Beckum, over objections from both sides of the Atlantic. Others commentors mention that Beckum was hearladed as the next Hernandez Brother at the time. Interesting stuff.

I always found it interesting that Gargunza’s desire “to live forever in a perfect body” was such that he was utterly willing, without concern or comment, to transfer his consciousness into a *female* body. Was Moore aware of, did he intend this as a homage to, the Golden-Age Superman villain(ess) The Ultra-Humanite?